This article was originally published on The Oscholars’ website in May 2015. I am republishing it here because it has since disappeared online, although there may be interest in it because of its high queer content, in addition to the beautiful art of course. If I had written the article now, I would have emphasized that queer element more. As I am currently too busy editing my Carel de Nerée biography and preparing for next year’s exhibition on De Nerée, I do not have time to write a new article on Sarluis. After Carel de Nerée, however, I would like to do more on Sarluis. Hopefully a book and an exhibition as well. For the time being, I don’t want to deprive my loyal fans of my wonderful articles for too long, hence this republication.

For most not even the name sounds familiar nowadays: Léonard Sarluis. Except maybe when one has a more than passing interest in symbolist art or a similar interest in the life and times of Oscar Wilde — and particularly his last days spent in Paris. Ellmann mentions Sarluis just once as one of the about fifteen persons present at Wilde’s funeral. In most Wilde biographies his name is usually missing. The internet teaches us a little more about Sarluis but to the English-speaking Wilde-scholars his being originally Dutch may present a problem for substantial archival research. New archival research allows us to give Sarluis a little more depth than just a beautiful young man favoured by Oscar. Sarluis appears to be an interesting person and talented artist in his own right.

Sarluis

Salomon Leonard Sarluis was born 21 October 1874 in The Hague as a son from the Jewish dealer in antiques Salomon Sarluis. His name is sometimes also spelled Sarlouis or Sarluys. Father Sarluis’ store in the Spuistraat was renowned for its beauty. In the minor classic of Dutch fin de siècle literature Het jongetje (The Little Boy, 1898) by Henri Borel (1869-1933) the young protagonist admires the store ‘waar al die vreemde, mooie dingen waren’ (‘where there were all these peculiar, beautiful things’). This background seems to have been of some importance for the young artist to be. One description does indeed read as if he were a personage from a decadent novel who from an early age is destined for all things beautiful and refined:

Issu d’une vieille famille de riches antiquaires israélites, la féerie commença pour Sarluis dès son plus jeune âge où, dans les galléries paternelles, ses jouets familiers furent des objets d’art, sa recréation, la contemplation d’anciens tableaux aux sujets mystérieux. Sa vie commence comme un conte d’Hoffmann, elle se poursuivra de le même manière avec une étrange mélange de mysticisme et de jouissances esthétiques. Né dans un musée, élevé chez lui en raison de sa santé délicate, apprenant l’histoire dans le Satyricon de Pétrone et dans la Bible, dès l’age de treize ans le dessin s’impose à Sarluis comme un exutoire nécessaire à son imagination débordante.

[Descendant of a long-established family of rich Jewish antique dealers, wonderland began for Sarluis from his earliest years, where in his father’s galleries, his everyday toys were objets d’art and his recreation the contemplation of ancient paintings with mysterious subjects. His life began like a tale by Hoffmann, and followed its course in the same way with a strange mixture of mysticism and æsthetic playfulness. Born in a museum, brought up at home because of his delicate health, learning history in Petronius’ Satyricon and the Bible, from the age of thirteen drawing was a compulsion for Sarluis as a necessary outlet for his burgeoning imagination. (Édouard-Joseph, Dictionnaire).]

His father places Sarluis at a financial institution in Hanover but instead of calculating and working hard Sarluis takes riding lessons from young cavalry lieutenants. The boisterous young men also visit Sarluis at his place of work, to the great shame and anger of his employer. According to Édouard-Joseph this actually was the reason for his bankruptcy and eventual suicide.

Banking wasn’t a success anyhow and his father allows him to become an artist. A painter friend from his father insists on Leonard entering The Hague Academy of Arts. He receives artistic schooling there from 1891-1893. In these years he starts using the name ‘Leonard’ as a tribute to Leonard da Vinci. And his father also furnishes his son with an atelier of his own. Aged just eighteen Sarluis paints his first monumental works. Works which are possibly more neo-Byzantine than symbolist. At least one of these earliest works, now lost, must have been a quite decadent tableau:

A l’áge de dix-huit ans, il s’attaque à un tableau de huit mètres de long sur trois mètres de haut représentant une sorte d’orgie où des éphèbes grecs se prélassaient dans une palais hanté par des lions; c’était un délire de couleurs flamboyantes qui manquait de method et de dessin et qui, donné à un prince russe pour son château de l’Ukraine fut détruit depuis par la révolution bolcheviste. (Édouard-Joseph)

[At the age of eighteen, he threw himself into a painting eight metres wide by three metres high, representing a sort of orgy where Greek ephebes sprawled about in a palace infested with lions; it was a delirium of flamboyant colours which lacked both method and technique, and which, given to a Russian prince for his castle in the Ukraine, was subsequently destroyed in the Bolshevik revolution.]

More, or perhaps most, of the earliest, pre-1900 works by Sarluis seems to have suffered the fate of being lost by the way. As far as could be determined, no Dutch museum has any work by one of the most remarkable of Dutch symbolists.

An extravagant theme such as this is more reminiscent of symbolist painters like Jean Delville or Gustave Moreau and as such is quite exceptional in Dutch painting from around 1890, then still dominated by the impressionist landscapes of The Hague School. Maybe someone like Jan Toorop or Lawrence Alma Tadema could have depicted such a voluptuous scene. One of Sarluis’ first exhibitions took place summer 1894 in The Hague and was immediately noticed:

Recht nieuwsgierig waren we eens iets te zien van het jonge licht, dat, volgens hetgeen er over geschreven is, daar zoo opeens in Den Haag als een ster van het eerste water aan den Haagschen kunsthemel is verschenen: de jonge Sarluis.

[Genuinely curious we were actually to see something of the bright young light which, according to that was written about it, all of a sudden shines so bright on the heavens of The Hague’s art world: the young Sarluis.] (Newspaper Nieuws van den Dag, June 6 1894)

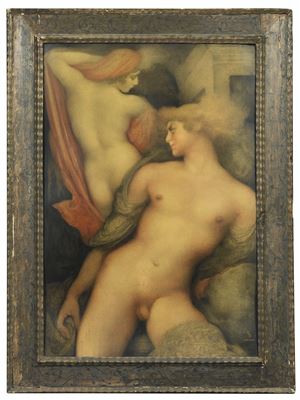

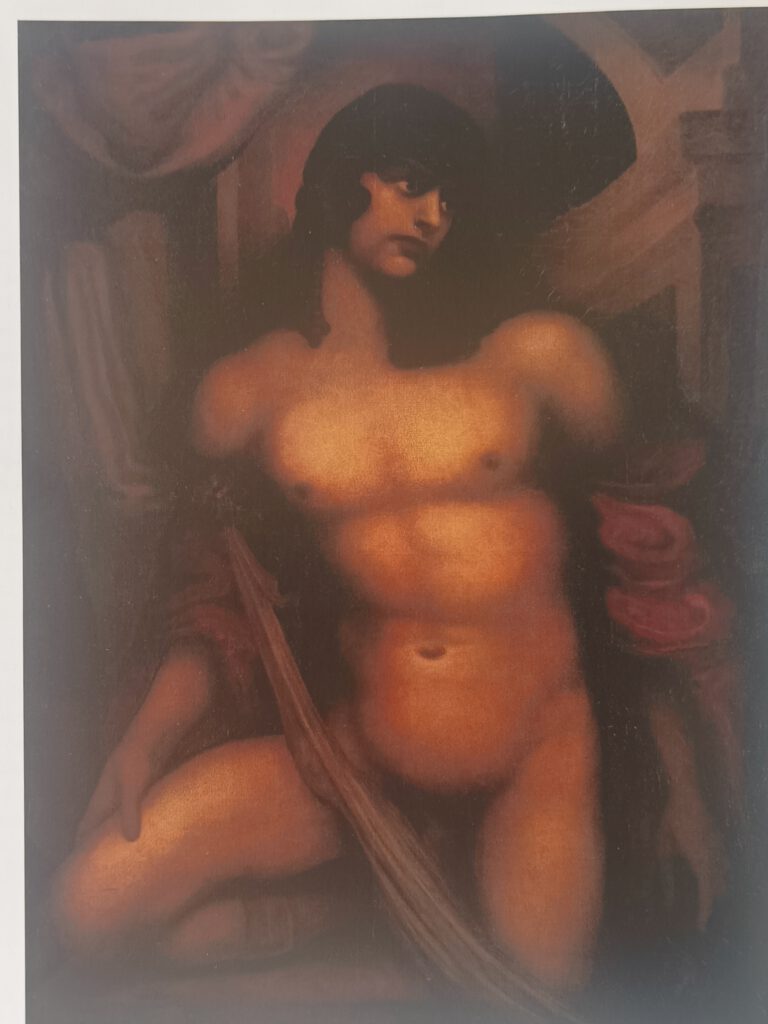

Sarluis manifests himself, or is ‘marketed’, as somewhat of a child prodigy, to the annoyance of some of the art critics. However it is, it must have been a curious sight at group exhibitions: Sarluis’ monumental, mythological male nudes side by side with land- and cityscapes by Israëls, Mesdag or Breitner. Some critics seem to have understood what Sarluis was trying to do, namely ‘terughalen van wat den grootsten idealisten voor den geest heeft gestaan’ (‘recall what the great idealists have had in mind’), writes one critic after a May 1895 group exhibition in Rotterdam. These idealists were of course the symbolist generation’s greatest heroes Plato and Da Vinci. At the Rotterdam exhibition Sarluis exhibited among others a painting depicting ‘Shakespearian lovers’ of ‘superior quality’. Reactions were generally mixed: some critics thought Sarluis was an untalented botcher who would never be more than a decoration painter. But curiously the great impressionist painter G.H. Breitner greeted Sarluis as ‘the new Rubens’. [See this recent article on Sarluis’ queerness and the reception in The Netherlands in the 1890s. S.B. 2024]

Paris

In 1894 Sarluis left for Paris to complete his artistic education. He would go and live there definitely only after 1904; till that time he commutes between Paris and The Hague, thus becoming an important cultural mediator. The Hague was, more than any Dutch city, focused on Paris and everything new and important that was happening there as far as literature and the arts were concerned. Pretty soon he was well up in Parisian avant garde art circles. Dutch artists already active and established in Paris such as Georges de Feure , ‘Henricus’ who also worked for Salis’ periodical Le Chat Noir), Jan Verkade (the Dutch Nabi) or the symbolist painter P.C. de Moor might have helped him on his way. Possibly the journalist Frits Lapidoth (who published Fransche teekenaars ‘French illustrators’ in 1894 and the Peladan-like decadent novel Goëtia, 1893) or Sarah Bernhardt’s Dutch impresario Joseph Schürmann might also have introduced the young painter Sarluis in these circles.

Who or however it is, Sarluis was introduced in Parisian avant garde circles early in 1896:

On February 26 1896 Armand Point ‘introduced’ him during a banquet given for Emile Verhaeren. As Gisèle Marie reported: ‘Sarluis was made to climb up on the table so all could contemplate this new phenomenon; Rachilde gave him an enthusiastic kiss.’ (Jumeau-Lafond p. 335)

This was the first and as far as could be determined the only Verhaeren banquet given during Wilde’s lifetime. So one wonders where or how Jullian – who of course never was averse to a tasty anecdote – got his slightly more romantic/erotic version of this presentation:

On one occasion, at the end of a banquet given in honour of Verhaeren, the Belgian poet was completely forgotten and a young Dutch-Jewish painter called Sarluis, whom La Jeunesse and Oscar had forced to stand on the table, had become the centre of attention. (Jullian p. 322-323)

In early 1896 Wilde was in prison and of course unable to visit. It is more probable that Wilde became acquainted with Sarluis in his last Parisian days of 1899-1900. Claims that Wilde had admired Sarluis’ work at London exhibitions could also not be substantiated with any proofs or documents but it is of course possible Wilde had seen some of Sarluis’ work before they met. By that time Sarluis was as well known as any of his French artist friends. His first artistic moment of fame came in November 1896 at the renowned gallery Georges Petit. Here he exhibited a large painting Nero and Agrippina, now also lost, which dates from 1894 and caused a scandal when it was first exhibited that year in The Hague. [Presumably because of homo-erotic nature. S.B. 2024] It was greatly admired by none other than Puvis de Chavannes. At the same time photos of this and other work by Sarluis exhibited at Petit were on view in the shop windows of bookstore Blok in his native town The Hague. In 1897 it would be on view again in The Hague and Sarluis would accompany his work (see Algemeen Handelsblad 3-3-1897). One of the visitors to the Petit gallery was the Dutch writer Louis Couperus who knew Sarluis from The Hague.

After having read and admired the English translation of Couperus’ decadent novel Noodlot (1890, Footsteps of Fate, 1892) Wilde had spontaneously sent Couperus a copy of The Picture of Dorian Gray. That copy has not turned up yet but some letters were exchanged and these have survived. There is no evidence that they actually met, though that of course is a possibility. Couperus’ letters never contain allusion to the modern world he lived in and are almost always short and formal. Couperus did visit London and Edmond Gosse and his friends suchs as Arthur Symons, de Wyzewa, Rothenstein or Robert Ross in June 1898. Wilde’s relation-to-be Alexander Teixeira de Mattos translated the Couperus novel Extaze (Ecstasy, 1892) and Jack T. Grein the Couperus debut Eline Vere (1889, transl. 1892).

Anyway, Couperus was not as impressed as Chavannes by Sarluis’ painting. In December 1896 he writes his cousin Constance Valettte (1878-1966):

Wij zijn hier op een expositie van Sarlouis geweest: Nero en Agrippa, een immens stuk, maar zoo brutaal humbug-achtig geklodderd, dat het afschuwelijk was! Maar hij bekent zelf, dat hij schildert pour épater le bourgeois en om rijk te worden!

[We have just been to a Sarluis exposition: Nero and Agrippina, an enormous work, but so brutally and rubbishly painted it was terrible! But he himself states he only paints pour épater le bourgeois and to get rich!]

Couperus adds: ‘Hij [Sarluis] heeft zijn jaren laten knippen, op raad van John Jacobson’ (‘He [Sarluis] had his hair cut, on John Jacobsons advice.’) The painter Jacobson (Jean Jonas, 1867-1926) was another mutual friend from The Hague who would settle in Paris definitely in 1899. He would exhibit at least one painting (titled Plaine de Cornay) at the Dutch pavilion of the 1900 Paris International Exhibition. Apparently Jacobson thought Sarluis’ haircut a maybe little too wild or feminine?

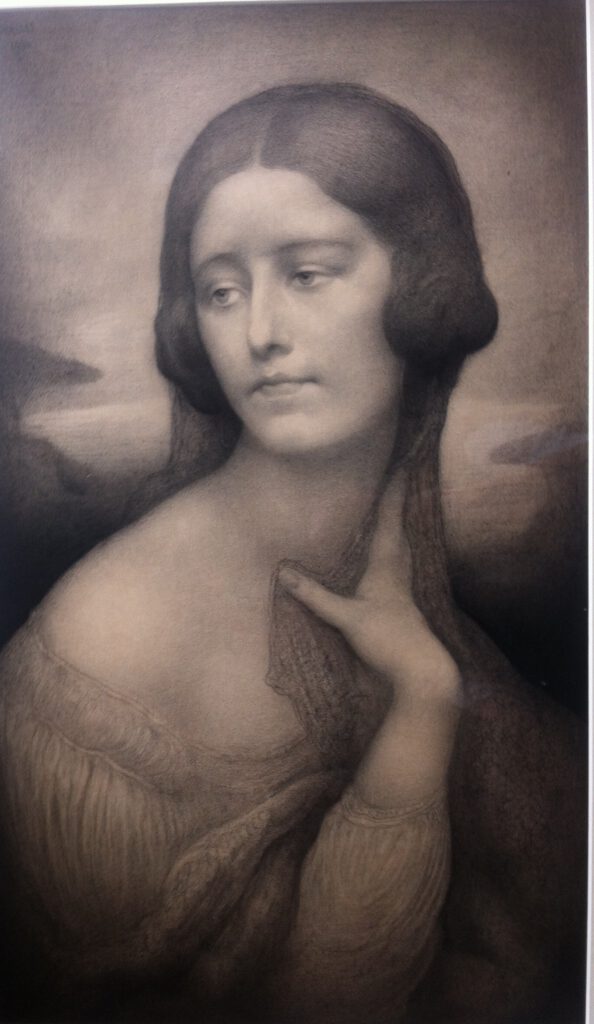

Jean Lorrain, ‘l’Oscar Wilde francais’, was greatly attracted by Sarluis and thought Sarluis had ‘le sourire d’une Vinci, les yeux de Donna Ligeia, le cou de la Beatrice de Dante Gabriel Rossetti.’ And the art critic Georges Soulier would also wrote admiringly about Sarluis’ work. Soulier apparently had a particular weakness for Dutch symbolists. He would also write positively (in Art et decoration) about Antoon van Welie (1866-1956): the young [gay, S.B. 2024] dandy from The Hague and ‘the last decadent painter’ had, thanks to his mentor Anatole France an exposition in the La Bodinière gallery early 1900. France was an acquaintance of Wilde’s, so possibly the Irish writer had admired Van Welie’s symbolist work there. Jean Lorrain admired Van Welie’s work as well and the Dutch artist would design the cover for the decadent writer’s novel L’Aryenne (1907).

Sarluis and Oscar Wilde most likely got to know each other in or soon after February 1898 when Wilde settled in Paris. Their most prominent mutual friend was the writer and journalist Ernest La Jeunesse. La Jeunesse would publish his memories of Wilde as early as December 1900.

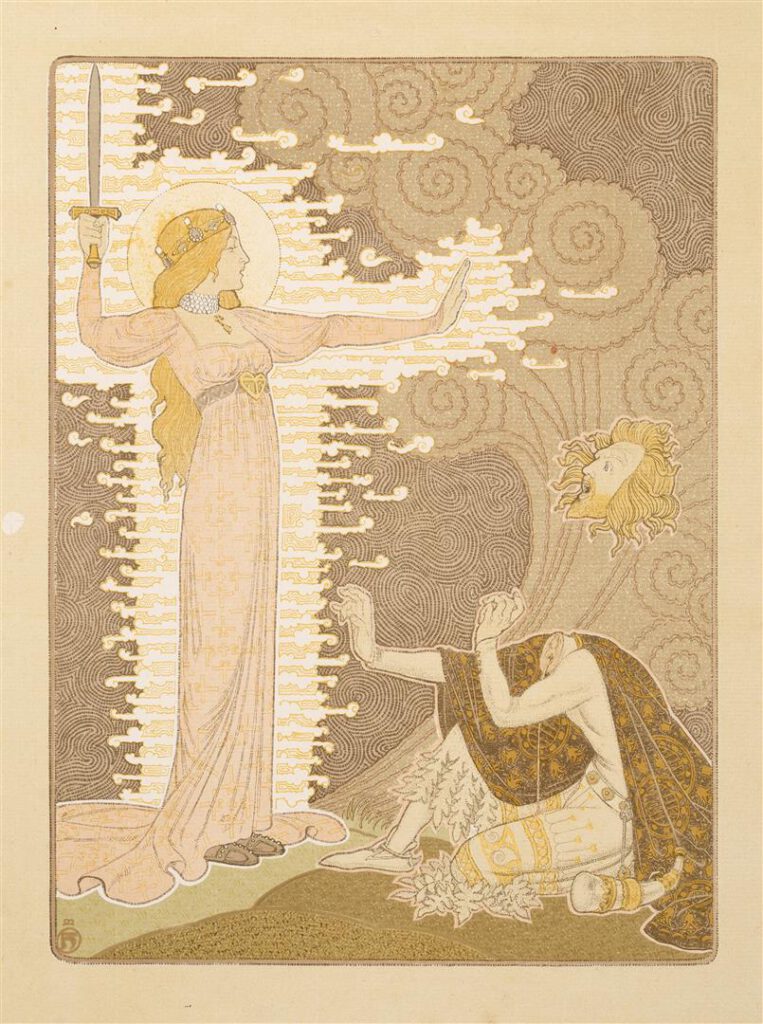

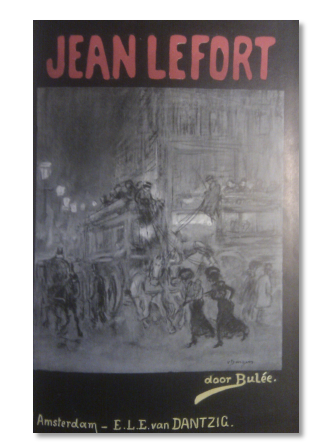

La Jeunesse appears to have known most of the Dutch writers and artist who lived in Paris around 1900 as well. In the autobiographical novel à cle which the Dutch journalist and French correspondent (from 1895 onwards) Charles Snabilíe wrote under pseudonym ‘Bulée’ Jean Lefort: een greep uit het Parijsche leven (1900. Jean Lefort: a slice of Parisian life) La Jeunesse appears under the thinly veiled literary disguise as the writer ‘Lavieillesse’. Other characters in the novel are based on people from Wilde’s circle as Catulle Mendès and Rachilde. Wilde himself does not feature though. Snabilié was great friends with the painter Kees van Dongen, who came to Paris for the first time in 1897 and would live there for most of his life. Jean Lefort has a cover design by Van Dongen. It is not recorded whether Van Dongen had any sympathy or interest in Wilde although as may be obvious they mingled in the same artistic circles. A friend of Van Dongen was the Dutch graphic artist Pieter Dupont who also lived in Paris. Van Dongen and Dupont would both exhibit at the Dutch pavilion at the International Exhibition 1900 (van Dongen designed the cover of the Dutch guide to the Expo) where Wilde might have seen these and other works by Dutch artists. It was probably Dupont, who was well into printing techniques and modern art (he made a famous portrait of Steinlen in 1901) who manufactured a little book of poems by Sarluis in 1898. Hommes! Voici le Messie has the imprint ‘P. Dupont, Paris’ and a preface by La Jeunesse.

The exact contents of the book are unknown to me unfortunately. No Dutch library has a copy of this rare little book, though online a copy is offered with a dedication by Sarluis to Wilde’s French translator Eugene Tardieu: ‘en neo-platocienne mais sincère amitié’ which gives some hint as to the neo-mystical contents.

Another interesting link between Wilde and Sarluis was Alfred Jarry. [In 1896 Jarry and Sarluis were lovers. S.B., 2024] In May 1898 Wilde and Jarry met for the first time, and they would only meet once more, but Wilde was important for Jarry and Jarry would keep sending the Irish writers his books. And not just Snabilíe but also Jarry present a literary alter ego of Sarluis. In his novel Les jours et les nuits (1897) the painter Raphaël Roissoy is based on Sarluis: ‘beau de traits et de s’être fait une tête, le corps trop femme du Saint Jean-Baptiste de Vinci.’ Jarry and Sarluis were friends and Jarry had visited Sarluis in The Hague June 1896.

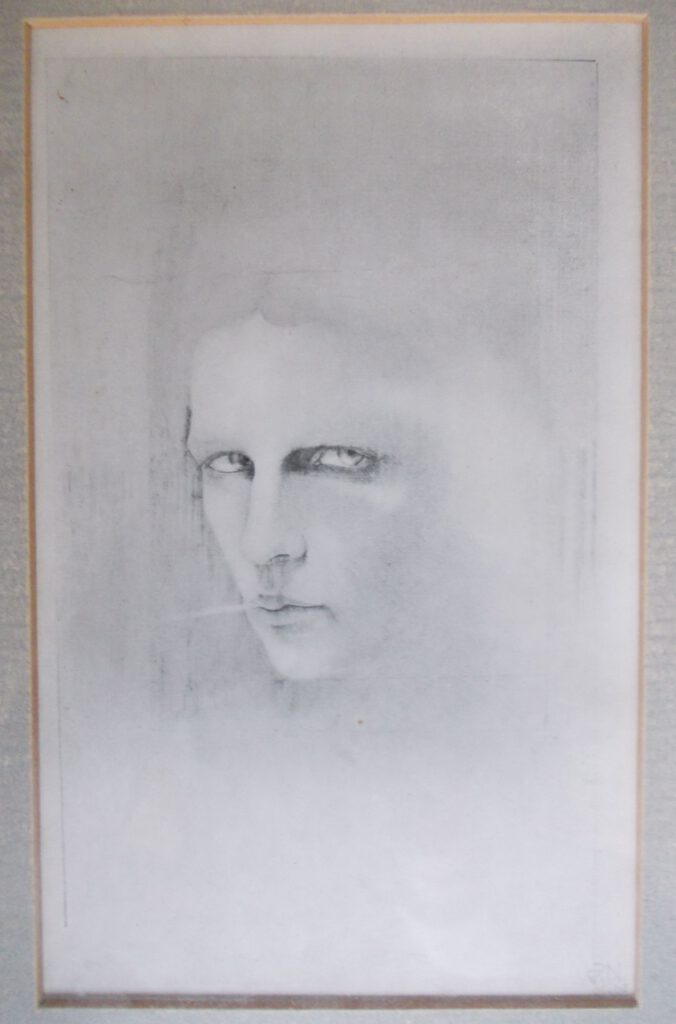

There was another [possibly gay, S.B. 2025] Dutch artist also who knew Sarluis and visited him and Wilde in Paris. About Carel de Nerée and Oscar Wilde we have written extensively. To that can be added a memoir of De Nerée’s good friend Hermine Schuylenburg who would remember later that when in Paris De Nerée ‘verkeerde in een kring van Da Vinci-bewonderaars’ (‘moved in circles of Da Vinci admirers’). One of them obviously was Sarluis. Though De Nerée never made monumental paintings like Sarluis, the influence of Da Vinci, especially his self-portraits, is clearly visible in De Nerée’s self-portrait in grey tones from 1901-1905.

Finally, whether Oscar Wilde ever admired Sarluis dancing on a table like a character in a Beardsley drawing is improbable. That they must have met several times on the Parisian boulevards and in cafés more than we know is quite probable. Proof that Sarluis affection and dedication to Wilde was sincere is to be found in his already mentioned presence at Wilde’s funeral.

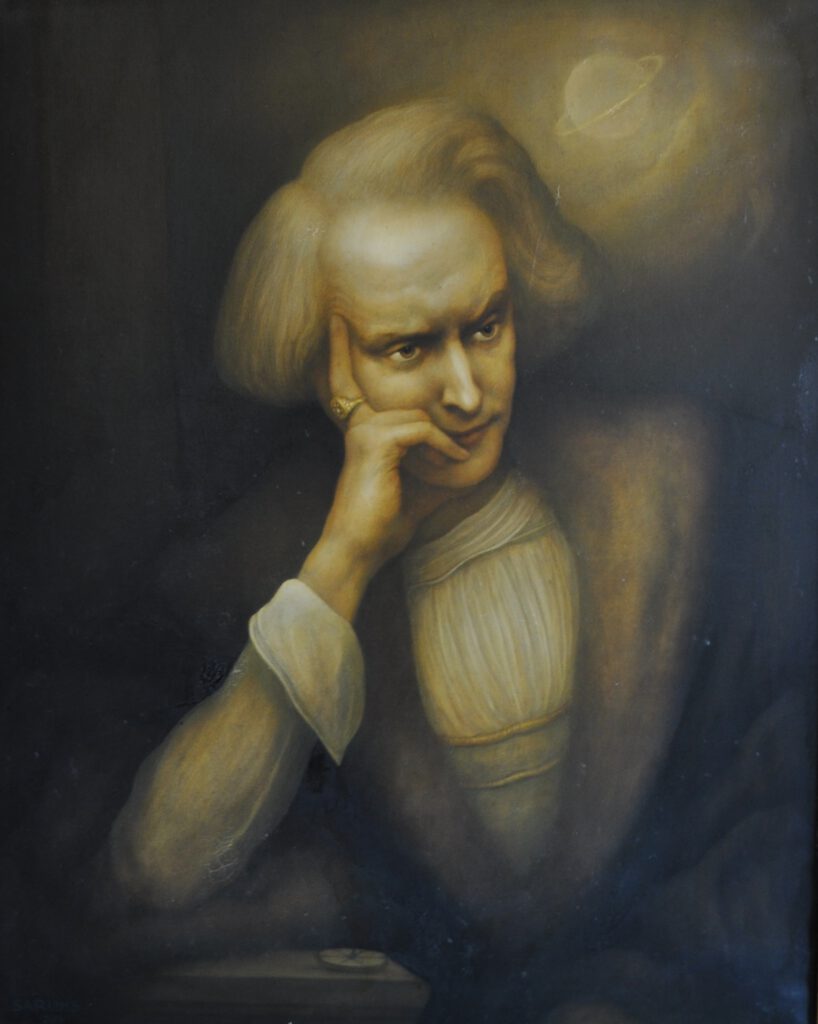

Sarluis’ life after 1900 would take a separate article. His later work, from around 1930 is arguably his best. For proof see for example the fine self portrait from 1932 (oil on canvas, 100 x 80 cm, Collection Jean-David Jumeau-Lafond, Paris) or Allegory: Lady in a landscape (pencil and conté on paper, 60 x 35 cm, private collection, The Netherlands) Both from 1932 and both reproduced here for the first time.

From a Wildeian perspective, one maybe little known or somewhat forgotten fact from these latter days must be mentioned. It was Sarluis who in the late 1920’s shared his memories, and more, of Wilde with none other than Coco Chanel, thus mediating between two icons of 20th century culture while being himself a forgotten icon of fin de siècle culture.

Nonetheless, Sarluis died [by suicide. S.B. 2024] forgotten and lonely on 20th April 1949 in his Parisian apartment. Aged 75, he was probably the last great Wildeian symbolist. [And a rare example of a Dutch queer artist from around 1900. De Nerée being the other exception. S.B. 2024]

Sources

Archives of the RKD (Netherlands Institute for Art History), The Hague.

Bastet, F., Louis Couperus. Een biografie. Amsterdam, 1987.

Bink, S., ‘Leonard Sarluis’, in: Pandora Magazine, 2015, nr. 2, p. 30-31

Bink, S., ‘About a possible non-fictional encounter between Oscar Wilde and Carel de Nerée’, https://rond1900.nl/?p=19678

Bink, S., Carel de Nerée tot Babberich en Henri van Booven: Den Haag in het fin de siècle. WBooks, 2014. (Published on the occasion of exhibition, curated by the author, at the Louis Couperus Museum, November 2014 – 2015 may).

Bink, S. ‘Een greep uit het Parijse leven van Kees van Dongen: over Jean Lefort (1900)’ https://rond1900.nl/?p=19826 .

Couperus, L. De correspondentie. Ed. H.T.M. van Vliet. Amsterdam, 2013.

Delpher.nl (online archive of Dutch historical newspapers).

Édouard-Joseph, René, Dictionnaire biographique des artistes contemporaines, 1910-1930. Paris, 1930-’36.

Ellmann, R., Oscar Wilde. Ed. New York, 1988.

Fell, Jill, ‘Oscar Wilde and Alfred Jarry’ http://www.oscholars.com/RBA/thirty-four/34.7/Articles.htm

Hopmans, A., De onbekende Van Dongen: vroege en Fauvistische tekeningen, 1895-1912. (English ed.: The Van Dongen Nobody Knows: Early and Fauvist Drawings 1895-1912). Rotterdam etc., 1997.

Julllian, Ph., Oscar Wilde. London etc., 1971.

Jumeau-Lafond, J.D., Painters of the Soul: symbolism in France. 2006.

Lieverloo, K. van a.o., Antoon van Welie: de laatste decadente schilder, 1866-1956. Waanders, 2007.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Hendrik_Breitner

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georges_de_Feure

[1] http://www.artfinding.com/40290/Biography/Jansen-Hendricus

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jan_Verkade

[1] http://www.artnet.com/artists/pieter-cornelis-de-moor/past-auction-resultshttp://www.artnet.com/artists/pieter-cornelis-de-moor/past-auction-results

[1] In October 1900, de Mattos married Lily Wilde, widow of Oscar’s brother Willie. Oscar Wilde died in November.

[1] The Picture of Dorian Gray as ‘Le Portrait de Dorian Gray’, Paris: Albert Savine October 1895.

[1] Collection Elysium Books, reproduced by kind permission.

[1] https://rond1900.nl/?p=19678

[1] http://www.baudelaire-chanel.com/a_baudelairean_destiny.php