Our motto, ‘All art is quite useless,’ derives from The Picture of Dorian Gray. Oscar Wilde makes a regular appearance here, just as the artist Carel de Nerée tot Babberich — the latter on account of his being a personal interest of yours truly. This time we present you with a — perhaps equally useless — article on the two of them, about a case of non-fictional reception, yes, about an encounter between the two artists that may have occurred in reality.

The final days of the great Irish writer in exile continue to appeal to the imagination, then and now. Some fans believe they can see Wilde among the 51 million visitors to the Paris World Exhibition in 1900; others speculate about the possibility that a recording of their hero’s voice has survived. The question of who saw and spoke to Wilde during his final days and who may have attended his funeral is a real sub-section of Wildean research. Even the tiniest details are of the greatest importance as befits the study of a near-saint. And in view of the fact that we of rond1900.nl do not despise such minutiae either, we are pleased to add yet another remarkable character to the list of loyal friends whom Oscar Wilde may have met shortly before his death.

You guessed it, didn’t you? Carel de Nerée tot Babberich. According to the Dutch publisher and amateur Wildean Johan Polak there were quite a few Dutchmen who visited Wilde during his last days, hanging on his lips on the Parisian boulevards. However, he provides us neither with sources nor any evidence to prove his assertion, while there is nothing to be found in his archive to bear him out. [1] We on the other hand shall meticulously present our case and our ‘evidence’ to you. In case we are guilty of serious errors of thought or misreadings, we shall be pleased to be corrected. We refer you to the forthcoming issue of the literary-historical magazineZacht Lawijd which contains my ample article on the friendship between De Nerée and Henri van Booven, followed by an extended bibliography, enumeration of sources and additional contextual information. What follows is a revised fragment from that piece.

The 1900 World Exhibition took place in Paris between 15 April and 12 November. It heralded the quasi-official introduction of art nouveau. Thus one could admire in the pavilion of Siegfried Bing (who had given the trend its name in 1895) designs of Georges de Feure, jewels of Lalique and dances of Loïe Fuller. If only we could have been present! Unfortunately we don’t have that privilege.

Things were different for Carel de Nerée who in May 1900 spent some time in Paris to see the new art he admired. In August of the same year he returned along with his friend, the painter Gustave van der Does, to see everything a bit longer and more thoroughly. These months were Oscar Wilde’s last summer. And the Paris World Exhibition was his final entertainment: ‘He was a man waiting for something, perhaps a miracle, only to find that it is death. During the summer of 1900 he had a new consolation, the International Exhibition.’ [2]

We know for sure that during these last days of his life Wilde was accompanied by Catulle Mendès, André Gide, Ernest La Jeunesse or Henry Bouchard. His Spanish friend, the artist Rubén Darío came to see him, as did Alfred Douglas. Wilde spent these days sauntering on and near the boulevards, enjoying a drink, often in the company of ‘fans’ and old friends. He was ‘unavoidable’ there. According to his biographer Ellmann he frequently rubbed shoulders in the Calisaya Bar with ‘Ernest La Jeunesse, Jean Moréas and others.’ Douglas remembers:

We know for sure that during these last days of his life Wilde was accompanied by Catulle Mendès, André Gide, Ernest La Jeunesse or Henry Bouchard. His Spanish friend, the artist Rubén Darío came to see him, as did Alfred Douglas. Wilde spent these days sauntering on and near the boulevards, enjoying a drink, often in the company of ‘fans’ and old friends. He was ‘unavoidable’ there. According to his biographer Ellmann he frequently rubbed shoulders in the Calisaya Bar with ‘Ernest La Jeunesse, Jean Moréas and others.’ Douglas remembers:

When I came to Paris from Chantilly, if I had not made an appointment with him beforehand I could always find him at the Grand Café or the Café de la Paix of a morning, or at the Café Julien or the Calisaya Bar of an afternoon.

To many, Wilde remained a hero even after the scandal; his name was famous the world over. Things were slightly different in The Netherlands; there he was, first and foremost, notorious and far from being a self-evident presence in the cultural and literary discourse around 1900, with the exception of the circles frequented by a few more progressive Dutch artistic fellows. Thus the almost unknown Oscar Wilde had met the Dutch poet Jacques Perk in the Ardennes in 1879, while Willem Kloos had got to know Wilde’s poetry at an early date. [3] His work and reputation subsequently spread across Holland on a moderate scale. Interestingly, the Dutch translation (1893) of his play Salomé (written in French) pre-dates Alfred Douglas’s English version which appeared in 1894. 1893 is also the year that sees the Dutch translation of The Picture of Dorian Gray, a joint effort of Louis Couperus and his wife who corresponded about this project with the author. Wilde in his turn read and appreciated Footsteps of Fate (1892), the English translation of Couperus’s Noodlot (1890). After that there is not much to do about Wilde in The Netherlands. From 1905-1910 more translations appear and his stage works take their place among the stock repertoire.

Carel de Nerée tot Babberich and his close friend Henri van Booven were early and avowed admirers of Wilde. In his 1911 obituary of his artist friend who had died young, Van Booven typified their friendship as ‘Wilde and Beardsley.’ Previously, in an autobiographical novel from 1906, he had written that Wilde and Beardsley were ‘worshipped as if they were gods.’ Van Booven presented De Nerée with a copy of The Early Work of Aubrey Beardsley which stimulated the recipient’s visual aspirations. A literary trace of De Nerée can be found in Van Booven’s first volume of poetry, Witte nachten (White Nights). It contains a poem dedicated to him, ‘De avonduren’ (‘Evening Hours’) which evokes the evenings they spent together, reading and drawing. A disguised De Nerée appears elsewhere in Van Booven’s work, for instance in his novel Tropenwee (Tropical Misery, 1904) and in his collection Sproken (Fairy Tales, 1907 and 2nd. ed. 1915). And we meet De Nerée in Van Booven’s roman à clef Een liefde in Spanje (Love in Spain), describing a visit in 1901 to De Nerée in Madrid where the artist, employed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was staying for a while. The novel was only published in book form in 1928, but Van Booven had begun work on it at the end of 1901 and pre-publications appeared in magazines, in part after De Nerée’s death.

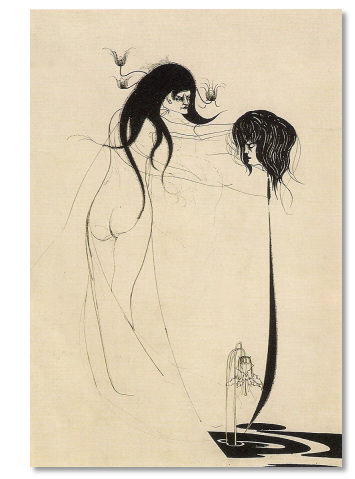

The Picture of Dorian Gray was an important book to De Nerée. In a letter from 1904 to his friend, the Dutch art critic Albert Plasschaert he wrote: ‘Critically I am on the side of Wilde (as expressed in his preface to Dorian Gray).’ His friend Hermine Schuijlenburg remembers that Salomé ‘greatly influenced’ him. Indeed, De Nerée made a Salomé illustration in Beardsley’s style in 1900- 1901. The ‘decadent,’ subversive subtext of Wilde’s work and its iconic status for the (homosexual) underground may well have contributed to De Nerée’s appreciation. For according to Plasschaert he shared ‘Oscar Wilde’s position towards women.’ Van Booven, too, alludes more than once to De Nerée’s being ‘different from the others.’ Of course it is difficult to ascertain if he really was homosexual or bisexual; his numerous affairs with ladies do point in another direction. It was Van Booven who really provided the written and literary connection between De Nerée and Wilde.

De Nerée was still alive when in January 1909 Van Booven began pre-publication in literary periodicals of parts of his novel Een Haagsch verhaal – Enkele waarachtige gebeurtenissen uit het leven van een geschoolden en begaafden beuzelaar en menschenhater (A Tale from The Hague. Some True Events from the Life of an Educated and Talented Tattler and Misantrope); it is therefore quite possible that De Nerée read the text. (The book appeared in volume form in 1912.) He cannot have done so with pleasure since the novel’s protagonist, a dandy called De Lacy — clearly based on De Nerée —, is not exactly portrayed in a flattering way. Van Booven makes De Nerée’s alter ego conspicuously defend Oscar Wilde, for in the novel De Lacy asks if he ‘may draw your attention to the fact that Oscar Wilde, whom you think is a criminal and a despicable homosexual, may be looked upon as one of our first apostles?’ This quotation shows that Van Booven did not lack courage, for at that time Wilde was primarily seen in Holland as an immoral character rather than as a writer of talent.

De Nerée was still alive when in January 1909 Van Booven began pre-publication in literary periodicals of parts of his novel Een Haagsch verhaal – Enkele waarachtige gebeurtenissen uit het leven van een geschoolden en begaafden beuzelaar en menschenhater (A Tale from The Hague. Some True Events from the Life of an Educated and Talented Tattler and Misantrope); it is therefore quite possible that De Nerée read the text. (The book appeared in volume form in 1912.) He cannot have done so with pleasure since the novel’s protagonist, a dandy called De Lacy — clearly based on De Nerée —, is not exactly portrayed in a flattering way. Van Booven makes De Nerée’s alter ego conspicuously defend Oscar Wilde, for in the novel De Lacy asks if he ‘may draw your attention to the fact that Oscar Wilde, whom you think is a criminal and a despicable homosexual, may be looked upon as one of our first apostles?’ This quotation shows that Van Booven did not lack courage, for at that time Wilde was primarily seen in Holland as an immoral character rather than as a writer of talent.

In his unpublished autobiographical novel Stille wateren (Silent Waters, 1951), which contains memories of his friendship with De Nerée, Van Booven strongly implies that De Nerée did meet Wilde. This novel, as well as other letters and memories of Van Booven, are founded in truth as much as possible, insofar as this can be ascertained, so there is hardly any reason to doubt their veracity. In answer to the question: ‘And what about you?—what are your plans?’ Van Booven makes De Nerée’s fictional alter ego respond:

A few old acquaintances from my time in Antwerp are presently living in Montmartre, making a name for themselves. We take a look in the most obscure forests of the city, just to watch. My friends know some famous organisms: Catulle Mendès, Ernest La Jeunesse among others. Oscar Wilde is out of prison. Rumour has it that he will come to Paris. We shall try to meet him.

De Nerée’s ‘time in Antwerp’ was between 1895 and 1897, when he attended the commercial school there. He frequented artists from various countries who were studying at the Academy of the Visual Arts. Their identities are as yet unknown. He also went to Brussels quite often, where his mother, an artist in her own right, was taught by Constant Meunier.

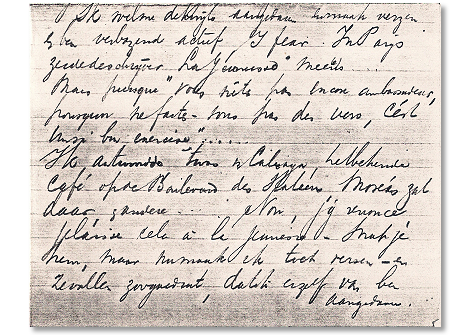

Schuijlenburg remembers that in Paris De Nerée and Van der Does rubbed shoulders ‘with a circle of painters and writers such as Jean Moréas.’ There is a letter in De Nerée’s archive, dated 9 October 1901, addressed to his beloved Claartje Rijnbende (1881-1971), to whom he retails the following anecdote:

In Paris the writer Ernest La Jeunesse said to me: ‘But since you are not an ambassador yet, why not write poetry? It’s such a good exercise…’ I answered (it was in Calisaya, the well-known café on the Boulevard des Italiens, Moréas used to go there, & others…): ‘No, I won’t do that, I leave that to youth.’ [‘Non, j’y renonce, je laisse cela à la jeunesse.’ ] — You get the joke? But all the same I am writing poems now and they are so good that I myself am touched.

The above provides, in addition to a later literary reminiscence of Schuijlenburg, evidence that in Paris De Nerée did indeed know Moréas and La Jeunesse and also that he did frequent the Calisaya bar. The dots following ‘and others’ may well be significant: it was unwise to talk about or to associate yourself with Oscar Wilde if one were employed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as De Nerée was, if one had diplomatic ambitions, if one belonged to a patrician family or if one moved in the posh circles of The Hague and elsewhere. De Nerée must have spoken of his Parisian adventure to Van Booven and other friends. Unfortunately De Nerée’s letters to Van Booven were lost during the Second World War, but as we have seen Van Booven did refer to it in his autobiographical novel. The secrecy surrounding De Nerée’s possible meeting with Wilde gets underlined when in the letter quoted above he recommends The Picture of Dorian Gray to Rijnbende with the remark: ‘Don’t mention this,’ which may be read as ‘don’t mention this in public.’ What else happened to him in Paris and whom he met there remains a mystery which should certainly be elucidated. When in 1904 Plasschaert suggests organizing an exhibition of De Nerée’s works in The Hague and in Paris, De Nerée’s answer is hesitant and dismissive. But what he adds is altogether remarkable: ‘The French always greatly encouraged me — they spoke of a huge success etc. in Paris.’ Perhaps De Nerée had been carrying some of his drawings in the summer of 1900? The years 1900 and 1901 proved highly prolific for him. He might have shown Wilde and/or others his own version of Salomé and other works at the time. A fascinating possibility.

De Nerée had easy access to Wilde’s circle. The French-Dutch symbolist painter Léonard Sarluis (1874-1949) was an old acquaintance of De Nerée and his brother Frans. Sarluis settled in Paris in 1894 and became part of a cénacle of writers and painters such as Jean Lorrain, Élémir Bourges, Alfred Jarry and Armand Point. He travelled between The Hague and Paris until 1904. Jarry, known to Wilde, took Sarluis as his model for the painter Raphael Roissoy in his roman à clef from 1897, Les Jours et les nuits. He contributed a foreword to Sarluis’s little book Hommes! Voici le Messie (1898). Sarluis had various expositions in Paris during the 1890s and designed with Point the poster for the Salon de la Rose-Croix in 1895. Oscar Wilde had previously admired his work in London in 1895. This admiration was extended to Sarluis’s physical appearance:

On one occasion, at the end of a banquet given in honour of Verhaeren, the Belgian poet was completely forgotten and a young Jewish-Dutch painter called Sarluis, whom Oscar had forced to stand on the table, had become the centre of attention. [4]

Sarluis was also among those few who attended Wilde’s funeral on 3 December 1900. Incidentally, De Nerée was by then back in The Hague. Rubén Darío, to whom we have already referred, may also have been a go-between. He was a poet as well as an ambassador. De Nerée, who aspired to become an ambassador, may well have met him. In any case they shared a love for Beardsley’s work as is borne out by Darío’s poem ‘Dream.’

Or take the sculptor Henry Bouchard (1875-1960). Van der Does attended the Académie Julian in Paris, as did Bouchard. Perhaps, but this is speculation, Louis Couperus may have been another link. Couperus knew both Sarluis and Oscar Wilde. It cannot be proved at present if Wilde and Couperus ever met in the flesh because of the loss of virtually their complete correspondence; but there are indications —there is certainly anecdotal evidence from family members —, that De Nerée and Couperus knew one another in the small world that was The Hague.

In 1911 Couperus, writing a prose piece called ‘Dorian Gray,’ described a meeting with the model for Wilde’s most famous character. Now that was pure fiction. But that the ‘Louis Couperus of the portcrayon’ really met the creator of Dorian Gray, or might have been the only Dutchman to see him up close shortly before Wilde’s death may well have been a fact as we have argued here.

In November an exposition in the Louis Couperus Museum in The Hague will open, devoted to De Nerée tot Babberich. Many unknown items will be shown, his artworks based on Couperus’s books and his friendship with Henri van Booven taking centre stage.

___________________

Notes:

1.Oscar Wilde in Nederland, 1988, and a communication by Koen Hilberdink.

2. The quotations from Ellmann, Oscar Wilde, 3rd ed., 1988, p. 577 ff.

3. See Ellmann p. 129 & J.D.F. van Halsema, Vrienden en visioenen, 2010, p. 204 ff.

4. Ph. Jullian, Oscar Wilde, 1968, p. 322-323.

5. Couperus, Van en over mijzelf en anderen, 1914.

(De Nerée’s and Van Booven’s letters and documents are kept in private collections.)

___________________

Illustrations:

– Fragment of a letter, Octobre, 1901.

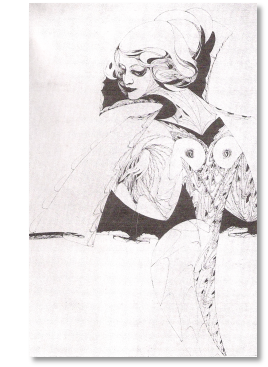

– Carel de Nerée tot Babberich, ‘Dans la nuit – idée’, 1904.

– Carel de Nerée tot Babberich, ‘Salomé’, 1900-’01.

Een mooi artikel!

Welk aanstaande nr van Zacht Lawijd bedoel je?

Jrg 13., nr 2 is mij gemeld. Dus niet dat nummer dat zag ik net hier en waarschijnlijk ook daar op mat viel!